Sitar maestro and Bharat Ratna Pandit Ravi Shankar passes away at 92 in San Diego

"suffered from upper-respiratory and heart issues over the past year and underwent heart-valve replacement surgery last Thursday. Though the surgery was successful, recovery proved too difficult for the 92-year-old musician."

Shankar, whose health had been fragile for the past several years, underwent heart-valve replacement surgery last Thursday at the Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, California where he breathed his last.

The music icon was admitted to the hospital last week when he complained of breathlessness.

"It is with heavy hearts we write to inform you that Pandit Ravi Shankar, husband, father, and musical soul, passed away today," his wife and daughter, Sukanya and Anoushka Shankar, said in a joint statement.

A recipient of Bharat Ratna in 1999 rpt 1999, Shankar maintained residences in both India and the United States.

He is survived by his wife Sukanya; daughter Norah Jones; daughterAnoushka Shankar Wright and husband Joe Wright; three grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

"As you all know, his health has been fragile for the past several years and on Thursday he underwent a surgery that could have potentially given him a new lease of life.

"Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of the surgeons and doctors taking care of him, his body was not able to withstand the strain of the surgery. We were at his side when he passed away," the joint statement said.

"We know that you all feel our loss with us, and we thank you for all of your prayers and good wishes through this difficult time. Although it is a time for sorrow and sadness, it is also a time for all of us to give thanks and to be grateful that we were able to have him as a part of our lives. His spirit and his legacy will live on forever in our hearts and in his music," they said in their joint statement.

A three-time Grammy award winner, Shankar last performed in California on November 4 along with his daughter Anoushka Shankar.

Shankar has also been nominated for the 2013 Grammys for his album "The Living Room Sessions Part-1" and was pitted against Anoushka in the same category.

"Shankar had suffered from upper-respiratory and heart issues over the past year and underwent heart-valve replacement surgery last Thursday. Though the surgery was successful, recovery proved too difficult for the 92-year-old musician," said another statement issued by the Ravi Shankar Foundation and East Meets West Music.

In recent months, performing, and especially touring, became increasingly difficult for the musician.

However, health couldn't prevent Shankar from performing with Anoushka on November 4 in Long Beach, California.

"This, in what was to be his final public performance, was in fact billed as a celebration of his tenth decade of creating music," the foundation said.

It said the memorial plans will be announced later.

A Bengali Brahmin, he was born Robindra Shankar on April 7, 1920 in Varanasi, the youngest of four brothers, and spent his first 10 years in relative poverty, brought up by his mother. He was almost eight before he met his absent father, a globe-trotting lawyer, philosopher, writer and former minister to the Maharajah of Jhalawar.

In 1930, his eldest brother Uday Shankar uprooted the family to Paris, and over the next eight years Shankar enjoyed the limelight in Uday's troupe, which toured the world introducing Europeans and Americans to Indian classical and folk dance.

As a performer, composer and teacher, Shankar was an Indian classical artist of the highest rank, and he spearheaded the worldwide spread of Indian music and culture, said writer and editor Oliver Craske, who provided additional narrative for Shankar's autobiography 'Raga Mala'.

Shankar achieved his greatest fame in the 1960s when he was embraced by the Western counterculture.

Through his influence on his great friend George Harrison, and appearances at the Monterey and Woodstock festivals and the Concert for Bangladesh, he became a household name in the West, the first Indian musician to do so.

Shankar has authored violin-sitar compositions for Yehudi Menuhin and himself, music for flute virtuoso Jean Pierre Rampal, music for Hosan Yamamoto, master of the Shakuhachi and Musumi Miyashita - Koto virtuoso, and has collaborated with Phillip Glass (Passages).

Harrison produced and participated in two record albums, "Shankar Family & Friends" and "Festival of India" both composed by Shankar.

Shankar also composed for ballets and films in India, Canada, Europe and the United States. The latter of which includes the films "Charly," "Gandhi," and the "Apu Trilogy".

A Magsaysay award winner, Shankar was nominated as a member of the Rajya Sabha in 1986.

Believing in the greatness of Indian classical music and blessed with charisma and intelligence, he pursued a dream of taking the music out to the Western world.

Between the early 1950s and the mid-1960s he became the leading international emissary for Indian music, first performing as a solo artist in the USSR in 1954, in Europe and North America in 1956, and Japan in 1958.

He developed a characteristic sitar sound, with powerful bass notes and a serene and spiritual touch in the alap movement of a raga.

The sitar virtuoso was responsible for incorporating many aspects of Carnatic ( south Indian) music into the north Indian system, especially its mathematical approach to rhythm. He also gave a new prominence to the tabla player in concert.

He was appointed Director of Music at the Indian People's Theatre Association, and later held the same position at All India Radio (1949?56). He composed his first new raga in 1945 (30 more would follow) and began a prolific recording career.

The music doyen wrote a new melody for Mohammed Iqbal's patriotic poem 'Sare Jahan Se Accha'.

The Bharat Ratna awardee started as a dancer with the group of his brother Uday Shankar but gave it up in 1938 to learn sitar under Allauddin Khan. During the tour of Uday's dance group in Europe and America in the early to mid-1930s, Shankar discovered Western classical music, jazz, and cinema, and became acquainted with Western customs.

The music doyen composed his first raga in 1945 and embarked on a prolific recording career. In the 1950s and 1960s, he became the unofficial international ambassador for Indian music, enthralling audiences in the USSR, Japan, North America. However, it was his association with Harisson that got him international stardom. In the 1970s, they collaborated on two albums and toured the USA together.

A Bengali Brahmin, Shankar was born Robindra Shankar on April 7, 1920 in Varanasi, the youngest of four brothers, and spent his first 10 years in relative poverty, brought up by his mother. He was almost eight before he met his father, a globe-trotting lawyer, philosopher, writer and former minister to the Maharajah of Jhalawar.

Legendary Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar, who influenced musicians ranging from The Beatles to violinist Yehudi Menuhin, has died aged 92 in the United States after surgery, his family said Wednesday.

Shankar, the father of American singer-songwriter Norah Jones and fellow sitar star Anoushka Shankar, died on Tuesday in hospital in San Diego, California, where he had undergone an operation to replace a heart valve.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh hailed Shankar, who popularised Indian classical music around the world, as "a national treasure and global ambassador of India's cultural heritage".

"An era has passed away... The nation joins me to pay tributes to his unsurpassable genius, his art and his humility," he said.

Shankar, who had houses in California and India, was born into a high-caste Bengali Brahmin family in the Hindu holy city of Varanasi in northern India on April 7, 1920.

He taught close friend the late Beatle George Harrison to play the sitar and collaborated with him on several projects, including the ground-breaking Concert for Bangladesh in 1971 to raise awareness of the war-wracked nation.

Harrison called him "Godfather of World Music" and Menuhin, himself widely considered one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, compared him to Mozart.

Other devotees included jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, whom he taught Indian improvisation techniques.

Shankar, a three-time Grammy winner, was also on the bill with Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix at the Woodstock Festival in New York state in 1969 when 500,000 people gathered for one of the iconic cultural events of the century.

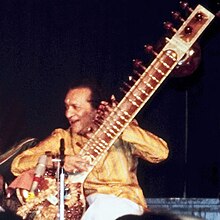

Dressed in traditional Indian clothes and seated on the floor when playing, he was lauded by the hippie generation but he expressed reservations about the excesses of Western stars and said his priorities were music, yoga and philosophy.

Shankar's wife Sukanya and his younger daughter Anoushka, 31, described him as a "husband, father, and musical soul".

"His health has been fragile for the past several years and (last) Thursday he underwent a surgery that could have potentially given him a new lease of life," they said in a statement.

"Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of the surgeons and doctors taking care of him, his body was not able to withstand the strain of the surgery. We were at his side when he passed away.

"Although it is a time for sorrow and sadness, it is also a time for all of us to give thanks."

His family and the Ravi Shankar Foundation said he had been suffering respiratory and heart problems.

The statement said that Shankar performed his last concert on November 4 in Long Beach, California, with Anoushka, who often played alongside him.

Shankar, who wrote the score for the 1982 Oscar-winning film "Gandhi", was survived by his second wife, two daughters, three grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

His son Shubendhra, born to his first wife, died in 1992.

The night before his surgery he was informed that his latest album, "The Living Room Sessions, Part 1", had received a 2013 Grammy nomination.

"Indian classical music has lost its chief ambassador," said A.R. Rahman, the country's leading composer who wrote the score for "Slumdog Millionaire".

Sanjay Sharma, whose family made sitars for Shankar for more than 30 years, told AFP that as a client he was demanding but appreciative.

"He was the biggest innovator in music," Sharma said. "He wanted to revolutionise the sitar as an instrument. It was very challenging to work with him but every moment spent with him was God's valuable gift to our family."

As a performer, composer and teacher, Shankar was an Indian classical artist of the highest rank, and he spearheaded the worldwide spread of Indian music and culture, said writer and editor Oliver Craske, who provided additional narrative for Shankar's autobiography 'Raga Mala'. Through his influence on Harrison, and appearances at the Monterey and Woodstock festivals and the Concert for Bangladesh, he became a household name in the West, the first Indian musician to do so.PTI reports.

Shankar also composed for ballets and films in India, Canada, Europe and the United States. He created music for the 'Apu Trilogy' by Satyajit Ray.

Credited with incorporating many aspects of Carnatic music in the north Indian classical system, Shankar was music director of All India Radio, New Delhi, from 1949 to 1956.

A three-time Grammy award winner, Shankar last performed in California on November 4 along with his daughter Anoushka Shankar.

Shankar has also been nominated for the 2013 Grammys for his album "The Living Room Sessions Part-1" and was pitted against Anoushka in the same category.

He was awarded the three top Indian national civil honours - Padma Bhushan in 1967, Padma Vibhushan in 1981, and Bharat Ratna in 1999.

Shankar befriended Richard Bock, founder of World Pacific Records, on his first American tour and recorded most of his albums in the 1950s and 1960s for Bock's label. The Byrds recorded at the same studio and heard Shankar's music, which led them to incorporate some of its elements in theirs, introducing the genre to Harrison.

The sitar legend authored violin-sitar compositions for Yehudi Menuhin and himself, music for flute virtuoso Jean Pierre Rampal, music for Hosan Yamamoto, master of the Shakuhachi and Musumi Miyashita - Koto virtuoso, and has collaborated with Phillip Glass (Passages).

A Magsaysay award winner, Shankar was nominated as a member of the Rajya Sabha in 1986.

Believing in the greatness of Indian classical music and blessed with charisma and intelligence, he pursued a dream of taking Indian music out to the Western world.

Shankar won the Silver Bear Extraordinary Prize of the Shankar won the Silver Bear Extraordinary Prize of the Jury at the 1957 Berlin International Film Festival for composing the music for the movie Kabuliwala.

He was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for 1962 and was named a Fellow of the academy for 1975. In 2001, Shankar was made an Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Elizabeth II for his "services to music". Shankar married Allauddin Khan's daughter Annapurna Devi in 1941 and had a son, Shubhendra Shankar.

He separated from Devi in 1940s. An affair with Sue Jones, a New York concert producer, led to the birth of Norah Jones in 1979. Jones became a successful musician, winning eight Grammy Awards in 2003. His second daughter Anoushka was born in 1981 with Sukanya Rajan, whom Shankar had known since the 1970s. He married Sukanya in 1989.

Ravi Shankar's exposure to the world of Indian culture was through his elder brother, the dancer Uday Shankar. He started touring with the troupe when he was just ten and became an integral part of the group in three years' time. In these interim three years, Ravi Shankar had taken to playing various musical instruments. However, his life-altering experience came in 1934 when he first heard Ustad Allauddin Khan, also known as simply 'Baba' (Father in Bengali) among his disciples and the man who completely reshaped the Maihar gharana of Indian classical music and would give the world the biggest ambassadors of Indian classical music.ibnlive reports:

Baba toured with Uday Shankar's troupe for a while and trained Ravi Shankar to play the sitar but it was sporadic. He told Ravi Shankar that he had to come and stay with him at his Maihar home to get full-fledged training. Then in the late 1930s, came the clouds of war as Nazi Germany went about consolidating its hold on the old parts of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Tours to Europe, the lifeline of Uday Shankar's troupe, dwindled and in 1938, at the age of 18, Ravi Shankar reached Baba's Maihar home.

There he would undergo the most rigorous training regime in any musical genre, part of it parts of folklore. As fellow students, Ravi Shankar had Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Indian classical music's first global ambassador and son of Ustad Allauddin Khan, Annapurna Devi (who would eventually become Ravi Shankar's first wife and as many connoisseurs still say was musically even more blessed than her husband), Pandit Nikhil Banerjee (the man whose sitar, they say, spoke to the audience), flutist Pandit Pannalal Ghosh, Maestro Rabin Ghosh who added the fifth string to the violin. As people would say it, training sessions could go up to 16 and even 18 hours a day in Baba's gurukul.

From his first public performance in 1939 in a jugalbandi with Ali Akbar Khan, Ravi Shankar moved to Mumbai in 1944 upon completing his training. A brief association with IPTA and a seven-year stint with the All India Radio in Delhi, would finally end in 1956 when he found his final calling - touring the west and popularising Indian classical music. Some observers say Ravi Shankar decided to make his move as he was amazed at the reception that Ali Akbar Khan got when he played in New York in 1956. Some say, the invitation had come to Ravi Shankar and since he was having problems with his marriage, he had suggested Ali Akbar Khan's name. Others are quick to point out that his marriage troubles had been there since the late 1940s and that would not have been a significant factor in turning down such an invitation in 1956.

The 1960s saw Ravi Shankar's western connections in full bloom. The Byrds were the first to be influenced by his music. His association with George Harrison of The Beatles would last from the 60s till the latter's death in 2001. George Harrison would buy a sitar, record 'Norwegian Wood', a composition drawing heavily from the Indian ragas, and would come to India to learn sitar from Ravi Shankar. In the transcendental 60s and 70s, Ravi Shankar was suddenly the big name who had arrived from the land of renunciation and peace. A collaboration with violinist Yehudi Mehunin won Pandit Ravi Shankar a Grammy. Countless performances followed including one at the Woodstock Music Festival (which he did not like) and one at the Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Gardens in New York City (of which he was a co-organiser along with Harrison).

Though Ravi Shankar started distancing himself from the Hippie movement from the beginning of the 1970s, his association with Harrison stood the test of time. In 1973, they recorded 'Shankar Family and Friends'. Harrison would later become the editor of Pandit Ravi Shankar's autobiography, titled 'Raga Mala'.

Ravi Shankar, in the meantime, had collaborated with Zubin Mehta, had scored music for the Richard Attenborough film 'Gandhi' (which won him an Oscar nomination for best original musical score along with George Fenton) and had become a Member of Parliament.

Connoisseurs, critics and contemporaries differ as to whether he was the greatest sitarist India produced in the 20th century. Names like Vilayat Khan, Nikhil Banerjee and even his first wife Annapurna Devi (though she played the Surbahar or bass sitar) frequently cropped up in these discussions. It is said that Annapurna Devi withdrew herself completely from public performances after her husband started touring extensively. Many say that she would have completely overshadowed her husband and that's why the conscious decision. Others feel Ravi Shankar deliberately wanted to keep her away as she was decidedly superior as some of their early Jugalbandi concerts proved. But since these recordings are non-commercial and are the preserve of a select few, these conversations have been held to be mostly in the realm of speculation. But Ravi Shankar's separation from Annapurna Devi definitely took a toll on the relationship between him and Ali Akbar Khan. The two would seldom play together later and even when they would occasionally create magic on the stage, offstage there would be no words exchanged.

But there is no point denying that barring possibly Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, no Indian classical musician, other than Pandit Ravi Shankar, has had such an impact on popularising Hindustani classical music across the oceans.

If Pandit Ravi Shankar's musical journey was one of rare vivacity colour, his personal life kept pace with these developments in the musical world. Married to Annapurna Devi in 1941, who gave birth to their son Shubho Shankar, they finally divorced after two decades though the cracks had started appearing in the 1940s themselves after Ravi Shankar started seeing a dancer, Kamala Shastri. A late-1970s affair with New York-based concert producer Sue Jones led to the birth of their daughter Norah Jones, who is today an accomplished musician herself and a recipient of 8 Grammys. Ravi Shankar separated from Kamala Shastri in 1981 and lived with Sue Jones till 1986. He married Sukanya Rajan in 1989 who had given birth to their daughter and sitarist Anoushka Shankar in 1981.

Was Ravi Shankar the greatest sitarist or classical musician India had ever produced? It is a difficult question to answer but there is no point denying that he was the one who took Indian music to faraway shores and created a foothold for the same in the west. But calling him the 'Godfather of world music', as George Harrison had once called him, would be too simplistic an expression. It was an exotic sound when it travelled west and hit those shores. But trained ears might reserve a different judgement.

Sitarist and composer Ravi Shankar, who helped introduce the sitar to the Western world through his collaborations with The Beatles, died in Southern California on Tuesday, his family said. He was 92.

Shankar, a three-time Grammy winner with legendary appearances at the 1967 Monterey Festival and at Woodstock, had been in fragile health for several years and last Thursday underwent surgery, his family said in a statement.

"Although it is a time for sorrow and sadness, it is also a time for all of us to give thanks and to be grateful that we were able to have him as a part of our lives," the family said. "He will live forever in our hearts and in his music."

In India, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's office posted a Twitter message calling Shankar a "national treasure and global ambassador of India's cultural heritage."

"An era has passed away with ... Ravi Shankar. The nation joins me to pay tributes to his unsurpassable genius, his art and his humility," Singh added.

Ravi Shankar's legacy is his music - Shujaat Khan: click here

For reactions on Ravi Shankar's death: click here

For slideshow on Ravi Shankar: click in.reuters.com/news/pictures/slideshow?articleId=INRTR3BGZH

Shankar had suffered from upper respiratory and heart issues over the past year and underwent heart-valve replacement surgery last week at a hospital in San Diego, south of Los Angeles.

The surgery was successful but he was unable to recover.

"Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of the surgeons and doctors taking care of him, his body was not able to withstand the strain of the surgery. We were at his side when he passed away," his wife Sukanya and daughter Anoushka said.

Shankar lived in both India and the United States. He is also survived by his daughter, Grammy-winning singer Norah Jones, three grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

Shankar performed his last concert with his daughter Anoushka on November 4 in Long Beach, California, the statement said. The night before he underwent surgery, he was nominated for a Grammy for his latest album "The Living Room Sessions, Part 1."

'NORWEGIAN WOOD' TO 'WEST MEETS EAST'

His family said that memorial plans will be announced at a later date and requested that donations be made to the Ravi Shankar Foundation.

Shankar is credited with popularizing Indian music through his work with violinist Yehudi Menuhin and The Beatles in the late 1960s, inspiring George Harrison to learn the sitar and the British band to record songs like "Norwegian Wood" (1965) and "Within You, Without You" (1967).

His friendship with Harrison led him to appearances at the Monterey and Woodstock pop festivals in the late 1960s, and the 1972 Concert for Bangladesh, becoming one of the first Indian musicians to become a household name in the West.

His influence in classical music, including on composer Philip Glass, was just as large. His work with Menuhin on their "West Meets East" albums in the 1960s and 1970s earned them a Grammy, and he wrote concertos for sitar and orchestra for both the London Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic.

Shankar served as a Rajya Sabha member from 1986 to 1992, after being nominated by then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

A man of many talents, he also wrote the Oscar-nominated score for 1982 film "Gandhi," several books, and mounted theatrical productions.

He also built an ashram-style home and music centre in India where students could live and learn, and later the Ravi Shankar Center in Delhi in 2001, which hosts an annual music festival.

Yet his first brush with the arts was through dance.

Born Robindra Shankar in 1920 in India's holiest city, Varanasi, he spent his first few years in relative poverty before his eldest brother took the family to Paris.

For about eight years, Shankar danced in his brother's Indian classical and folk dance troupe, which toured the world. But by the late 1930s he had turned his back on show business to learn the sitar and other classical Indian instruments.

Shankar earned multiple honours in his long career, including an Order of the British Empire (OBE) from Britain's Queen Elizabeth for services to music, the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, and the French Legion d'Honneur.

Ravi Shankar: 'Our music is sacred' – a classic interview from the vaults

To mark the sad death of the Indian sitar maestro, we visit Rock's Backpages – the world's leading archive of vintage music journalism – for this 1967 interview with KRLA Beat

"The message I'm trying to get through is that our music is very sacred to us and is not meant for people who are alcoholic, or who are addicts, or who misbehave, because it is a music which has been handed down from our religious background for our listeners."

The words are those of the famous Indian sitarist, Ravi Shankar, a man whose popularity in the United States has ridden the crest of the psychedelic movement.

But Shankar, in an exclusive Beat interview, made it clear that he didn't want to appeal to drug users or high hippies.

"If one hears this music without any intoxication, or any sort of drugs, one does get the feeling of being intoxicated. That's the beauty of our music. It builds up to that pitch. We don't believe in the extra, or the other stimulus taken, and that's what I'm trying my best to make the young people, without hurting them, of course, to understand."

Shankar refused the label of anti-drug preacher or social reformer. "I have nothing to say. No, it's the people's business if they want to drink, or smoke or take drugs. All I request is that these people just give me a couple of hours of sobriety or sober mind. That's all I request of them. Whatever they do before or after is not my business."

Popular now

The Indian musician admitted that his popularity has boomed in the US in the past two years, although he had been making tours of the States for the past 12 years.

"Many people, especially young people, have started listening to sitar since George Harrison, one of the Beatles, became my disciple. He is a beautiful person. His attitude toward our music is very sincere. He's very humble, and becoming better and better. His love for India and its philosophy and spiritual values is something outstanding.

Sitar school

Shankar described his music as having different stages in it resulting from many developments made on it over the centuries. "It has got the tremendously spiritual, the tranquil mood, then it drops into romantic, and, in the end, it is very playful and joyous."

Since Beatle George became so interested in the many moods of the sitar, other groups have taken it up, and, says Shankar. "It is now the 'in' thing."

Interest in the sitar has been increasing at such a great pace, Shankar decided to set up a sitarist school in Los Angeles. Indian music in general will be taught there, including a number of other Indian musical instruments and vocal training. "I'm going to be at the school for another two and a half months nearly teaching there," he said. "And even if I go, the school will function, as I'm trying to have a permanent staff."

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/dec/12/ravi-shankar-classic-interview

Pandit Ravi Shankar: The man and his women

He was a non-conformist from the very beginning. And perhaps, that attracted women towards Pandit Ravi Shankar. A gypsy at heart, the man found solace in perhaps music the most till a very late period of his life.

During his turbulent first marriage, Ravi Shankar had started seeing a dancer called Kamala Shastri, who allegedly had a big influence in Shankar's life. But just like a gypsy, he never really stuck to one woman and wandered around. He was unabashed about his fondness for women. In his autobiography, Raga Mala, he said: "I felt I could be in love with different women in different places. It was like having a girl in every port - and sometimes there was more than one!"

While Kamala and Panditji lived together as 'man and wife' till 1981, the musician also had affairs with two different woman, both of whom had daughters with him.

In New York, Ravi Shankar lived in with his concert producer Sue Jones and fathered her child Norah, who was born in 1979.

Meanwhile, he met a young Sukanya Rajan in 1972, who played the tanpura at his concerts. Even though the two were in committed relationships with other people (Sukanya was married, Shankar was in a relationship with Kamala Shastri and was also dating Sue Jones) they embarked on a relationship in 1978. They had a daughter, Anoushka, in 1981.

Although lovers, the couple did not enter matrimony till Anoushka was 8 years old. While Sukanya was desperate to get married to him in spite of him being with two other women, Shankar wasn't too sure.

"He was 58 then and told me he couldn`t change. I realised I was too much in love... I really couldn`t care. Even if he gave me a few days in a year, I was fine. That experience would help me tide over a whole year," Sukanya Shankar had said in an interview to The Times of India.

When Shankar decided to marry Sukanya, Sue decided to break ties with him and banned him from meeting Norah as well. By this time, his two decade long relationship with Kamala Shastri had also come to an end. And in 1989, Ravi Shankar married Sukanya and got stability that he longed for so many years.

"Raviji never had a real family life. He was too young when he was first married. When things crumbled, hurt, he took to touring abroad. He was a gypsy. Of course, there was Kamala (Shastri) aunty. But she too gave him freedom. I wanted to give him the home he never had," Sukanya said.

Home, stability, love and happiness is what the musician got from Sukanya Shankar. Not only did she accept him with his flaws (she 'blames' love for it) but embraced the people who came with him. Kamala Shastri and Suknaya shared a beautiful bond and the former apparently had even told Panditji once that marrying Sukanya was the best decision of his life.

The serenity that Panditji's music provided to generations was exactly the opposite of the kind of relationship he shared with various women in his life. It was tumultuous, caused heartbreaks and left some bitter memories. And yet, in spite of it, women wanted to nurture him, make him feel loved because he was truly one of a kind.

Ravi Shankar

| This article is about a person who has recently died. Some information, such as that pertaining to the circumstances of the person's death and surrounding events, may change as more facts become known. |

| Ravi Shankar | |

|---|---|

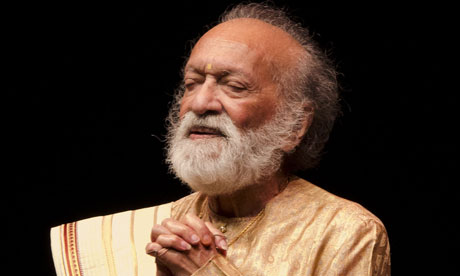

Shankar performs in Delhi in March 2009 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury |

| Born | 7 April 1920 Varanasi, United Provinces,Indian Empire |

| Died | 11 December 2012 (aged 92) San Diego, California, United States |

| Genres | Hindustani classical music |

| Occupations | composer, musician |

| Instruments | sitar |

| Years active | 1939–2012 |

| Labels | East Meets West Music[1] |

| Associated acts | Uday Shankar, Allauddin Khan,Ali Akbar Khan, Lakshmi Shankar, Yehudi Menuhin,Chatur Lal, Alla Rakha, George Harrison, Anoushka Shankar,Norah Jones, The Beatles, John Coltrane |

| Website | RaviShankar.org |

Ravi Shankar (Bengali: রবি শংকর; born Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury, 7 April 1920 – 11 December 2012[2]), often referred to by the title Pandit, was an Indian musician and composer who played the plucked-string instrument sitar. He has been described as the best known contemporary Indian musician.[3]

Shankar was born in Varanasi and spent his youth touring Europe and India with the dance group of his brother Uday Shankar. He gave up dancing in 1938 to study sitar playing under court musician Allauddin Khan. After finishing his studies in 1944, Shankar worked as a composer, creating the music for the Apu Trilogy by Satyajit Ray, and was music director of All India Radio, New Delhi, from 1949 to 1956.

In 1956, he began to tour Europe and the America playing Indian classical music and increased its popularity there in the 1960s through teaching, performance, and his association with violinist Yehudi Menuhin and rock artist George Harrison of The Beatles. Shankar engaged Western music by writing concerti for sitar and orchestra and toured the world in the 1970s and 1980s. From 1986 to 1992 he served as a nominated member of the upper chamber of the Parliament of India. Shankar was awarded India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, in 1999, and received three Grammy Awards. He continued to perform in the 2000s, often with his daughter, Anoushka.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Early life

Shankar was born on 7 April 1920 in Varanasi to a Bengali Brahmin family as the youngest of seven brothers.[4][5][6] Shankar's Bengali birth name was Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury.[4] His father, Shyam Shankar, a Middle Temple barrister and scholar who served as dewan of Jhalawar, used the Sanskrit spelling of the family name and removed its last part.[4][7] Shyam was married to Shankar's mother Hemangini Devi, but later worked as a lawyer in London, England.[4] There he married a second time while Devi raised Shankar in Varanasi, and did not meet his son until he was eight years old.[4] Shankar shortened the Sanskrit version of his first name, Ravindra, to Ravi, for "sun".[4]

At the age of ten, after spending his first decade in Varanasi, Shankar went to Paris with the dance group of his brother, choreographerUday Shankar.[8][9] By the age of 13 he had become a member of the group, accompanied its members on tour and learned to dance and play various Indian instruments.[5][6] Uday's dance group toured Europe and America in the early to mid-1930s and Shankar learned French, discovered Western classical music, jazz, and cinema, and became acquainted with Western customs.[10] Shankar heard the lead musician for the Maihar court, Allauddin Khan, in December 1934 at a music conference in Kolkata and Uday convinced the Maharaja of Maihar in 1935 to allow Khan to become his group's soloist for a tour of Europe.[10] Shankar was sporadically trained by Khan on tour, and Khan offered Shankar training to become a serious musician under the condition that he abandon touring and come to Maihar.[10]

[edit]Career

[edit]Training and work in India

Shankar's parents had died by the time he returned from the European tour, and touring the West had become difficult due to political conflicts that would lead to World War II.[11] Shankar gave up his dancing career in 1938 to go to Maihar and study Indian classical music as Khan's pupil, living with his family in the traditional gurukul system.[8] Khan was a rigorous teacher and Shankar had training on sitar and surbahar, learned ragas and the musical styles dhrupad, dhamar, and khyal, and was taught the techniques of the instruments rudra veena, rubab, and sursingar.[8][12] He often studied with Khan's children Ali Akbar Khan and Annapurna Devi.[11]Shankar began to perform publicly on sitar in December 1939 and his debut performance was a jugalbandi (duet) with Ali Akbar Khan, who played the string instrument sarod.[13]

Shankar completed his training in 1944.[5] Following his training, he moved to Mumbai and joined the Indian People's Theatre Association, for whom he composed music for ballets in 1945 and 1946.[5][14] Shankar recomposed the music for the popular song "Sare Jahan Se Achcha" at the age of 25.[15][16] He began to record music for HMV India and worked as a music director for All India Radio (AIR), New Delhi, from February 1949 to January 1956.[5] Shankar founded the Indian National Orchestra at AIR and composed for it; in his compositions he combined Western and classical Indian instrumentation.[17] Beginning in the mid-1950s he composed the music for the Apu Trilogy by Satyajit Ray, which became internationally acclaimed.[6][18] He was music director for several Hindi movies including Godaan and Anuradha.[19]

[edit]International career 1956–1969

V. K. Narayana Menon, director of AIR Delhi, introduced the Western violinist Yehudi Menuhin to Shankar during Menuhin's first visit to India in 1952.[20] Shankar had performed as part of a cultural delegation in the Soviet Union in 1954 and Menuhin invited Shankar in 1955 to perform in New York City for a demonstration of Indian classical music, sponsored by the Ford Foundation.[21][22] Shankar declined to attend due to problems in his marriage, but recommended Ali Akbar Khan to play instead.[22] Khan reluctantly accepted and performed with tabla (percussion) player Chatur Lal in the Museum of Modern Art, and he later became the first Indian classical musician to perform on American television and record a full raga performance, for Angel Records.[23]

Shankar heard about the positive response Khan received and resigned from AIR in 1956 to tour the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States.[24] He played for smaller audiences and educated them about Indian music, incorporating ragas from the South IndianCarnatic music in his performances, and recorded his first LP album Three Ragas in London, released in 1956.[24] In 1958, Shankar participated in the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the United Nations and UNESCO music festival in Paris.[14] From 1961, he toured Europe, the United States, and Australia, and became the first Indian to compose music for non-Indian films.[14] Chatur Lal accompanied Shankar on tabla until 1962, whenAlla Rakha assumed the role.[24] Shankar founded the Kinnara School of Music in Mumbai in 1962.[25]

Shankar befriended Richard Bock, founder of World Pacific Records, on his first American tour and recorded most of his albums in the 1950s and 1960s for Bock's label.[24] The Byrds recorded at the same studio and heard Shankar's music, which led them to incorporate some of its elements in theirs, introducing the genre to their friend George Harrison of The Beatles.[26] Harrison became interested in Indian classical music, bought a sitar and used it to record the song "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)".[27] This led to Indian music being used by other musicians and created the raga rock trend.[27]

Harrison met Shankar in London in 1966 and visited India for six weeks to study sitar under Shankar in Srinagar.[16][28][29] During the visit, a documentary film about Shankar named Raga was shot by Howard Worth, and released in 1971.[30] Shankar's association with Harrison greatly increased Shankar's popularity and Ken Hunt of Allmusic would state that Shankar had become "the most famous Indian musician on the planet" by 1966.[5][28] In 1967, he performed at the Monterey Pop Festival and won a Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance for West Meets East, a collaboration with Yehudi Menuhin.[28][31] The same year, the Beatles won theGrammy Award for Album of the Year for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band which included "Within You Without You" by Harrison, a song that was influenced by Indian classical music.[29][31] Shankar opened a Western branch of the Kinnara School of Music in Los Angeles, California, in May 1967, and published an autobiography, My Music, My Life, in 1968.[14][25] He performed at the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, and found he disliked the venue.[28] In the 1970s Shankar distanced himself from the hippie movement.[32]

[edit]International career 1970–2012

In October 1970 Shankar became chair of the department of Indian music of the California Institute of the Arts after previously teaching at the City College of New York, the University of California, Los Angeles, and being guest lecturer at other colleges and universities, including the Ali Akbar College of Music.[14][33][34] In late 1970, the London Symphony Orchestra invited Shankar to compose a concerto with sitar; Concerto for Sitar and Orchestra was performed with André Previn as conductor and Shankar playing the sitar.[6][35]Hans Neuhoff of Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart has criticised the usage of the orchestra in this concert as "amateurish".[3] George Harrison organized the charity Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, in which Shankar participated.[28] Interest in Indian music had decreased in the early 1970s, but the concert album became one of the best-selling recordings featuring it and won Shankar a second Grammy Award.[31][34]

During the 1970s, Shankar and Harrison worked together again, recording Shankar Family & Friends in 1973 and touring North America the following year to a mixed response after Shankar had toured Europe with the Harrison-sponsored Music Festival from India.[36] The demanding schedule weakened Shankar, and he suffered a heart attack in Chicago in November 1974, causing him to miss a portion of the tour.[37] In his absence, Shankar's sister-in-law, singer Lakshmi Shankar, conducted the touring orchestra.[37] The touring band visited the White House on invitation of John Gardner Ford, son of U.S. President Gerald Ford.[37] Shankar toured and taught for the remainder of the 1970s and the 1980s and released his second concerto, Raga Mala, conducted by Zubin Mehta, in 1981.[38][39]Shankar was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Music Score for his work on the 1982 movie Gandhi, but lost to John Williams' E.T.[40] He served as a member of the Rajya Sabha, the upper chamber of the Parliament of India, from 12 May 1986 to 11 May 1992, after being nominated by Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.[16][41] Shankar composed the dance drama Ghanashyam in 1989.[25] His liberal views on musical cooperation led him to contemporary composer Philip Glass, with whom he released an album,Passages, in 1990.[8]

Shankar underwent an angioplasty in 1992 due to heart problems, after which George Harrison involved himself in several of Shankar's projects.[42] Because of the positive response to Shankar's 1996 career compilation In Celebration, Shankar wrote a second autobiography, Raga Mala, with Harrison as editor.[42] He performed in between 25 and 40 concerts every year during the late 1990s.[8]Shankar taught his daughter Anoushka Shankar to play sitar and in 1997 became a Regent's Lecturer at University of California, San Diego.[43] In the 2000s, he won a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album for Full Circle: Carnegie Hall 2000 and toured with Anoushka, who released a book about her father, Bapi: Love of My Life, in 2002.[31][44] Anoushka performed a composition by Shankar for the 2002 Harrison memorial Concert for George and Shankar wrote a third concerto for sitar and orchestra for Anoushka and theOrpheus Chamber Orchestra.[45][46] In June 2008, Shankar played what was billed as his last European concert,[32] but his 2011 tour includes dates in the United Kingdom.[47]

Shankar performed his final concert, with daughter Anoushka, on November 4, 2012 at the Terrace Theater in Long Beach, California.

[edit]Style and contributions

Shankar developed a style distinct from that of his contemporaries and incorporated influences from rhythm practices of Carnatic music.[8] His performances begin with soloalap, jor, and jhala (introduction and performances with pulse and rapid pulse) influenced by the slow and serious dhrupad genre, followed by a section with tabla accompaniment featuring compositions associated with the prevalent khyal style.[8] Shankar often closed his performances with a piece inspired by the light-classical thumri genre.[8]

Shankar has been considered one of the top sitar players of the second half of the 20th century.[3] He popularized performing on the bass octave of the sitar for the alap section and became known for a distinctive playing style in the middle and high registers that used quick and short deviations of the playing string and his sound creation through stops and strikes on the main playing string.[3][8] Narayana Menon of The New Grove Dictionary noted Shankar's liking for rhythmic novelties, among them the use of unconventional rhythmic cycles.[48] Hans Neuhoff of Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart has argued that Shankar's playing style was not widely adopted and that he was surpassed by other sitar players in the performance of melodic passages.[3] Shankar's interplay with Alla Rakha improved appreciation for tabla playing in Hindustani classical music.[3] Shankar promoted the jugalbandi duet concert style and introduced newragas, including Tilak Shyam, Nat Bhairav and Bairagi.[8]

[edit]Recognition

Shankar won the Silver Bear Extraordinary Prize of the Jury at the 1957 Berlin International Film Festival for composing the music for the movie Kabuliwala.[49] He was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for 1962,[50] and was named a Fellow of the academy for 1975.[51] Shankar was awarded the three highest national civil honours of India: Padma Bhushan, in 1967, Padma Vibhushan, in 1981, and Bharat Ratna, in 1999.[52] He received the music award of the UNESCO International Music Council in 1975, three Grammy Awards, and was nominated for an Academy Award.[14][31][40] Shankar was awarded honorary degrees from universities in India and the United States.[14] He received the Kalidas Samman from the Government of Madhya Pradesh for 1987–88, the Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize in 1991, the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1992, and the Polar Music Prize in 1998.[53][54][55][56] In 2001, Shankar was made an Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Elizabeth II for his "services to music".[57] Shankar was an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and in 1997 received the Praemium Imperiale for music from the Japan Art Association.[8] The American jazz saxophonist John Coltrane named his son Ravi Coltrane after Shankar.[58] In 2010, Shankar received an Honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of Melbourne, Australia.

[edit]Personal life and family

Shankar married Allauddin Khan's daughter Annapurna Devi in 1941 and a son, Shubhendra Shankar, was born in 1942.[12] Shankar separated from Devi during the 1940s and had a relationship with Kamala Shastri, a dancer, beginning in the late 1940s.[59] An affair with Sue Jones, a New York concert producer, led to the birth of Norah Jones in 1979.[59] In 1981,Anoushka Shankar was born to Shankar and Sukanya Rajan, whom Shankar had known since the 1970s.[59] After separating from Kamala Shastri in 1981, Shankar lived with Sue Jones until 1986. He married Sukanya Rajan in 1989.[59]

Shubhendra "Shubho" Shankar often accompanied his father on tours.[60] He could play thesitar and surbahar, but elected not to pursue a solo career and died in 1992.[60] Norah Jones became a successful musician in the 2000s, winning eight Grammy Awards in 2003.[61]Anoushka Shankar was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album in 2003.[61] Anoushka and her father were nominated for Best World Music Album at the 2013 Grammy Awards for separate albums.[62]

Shankar was a Hindu and a vegetarian.[63][64] He lived with Sukanya in Encinitas, California.[65]

[edit]Death

On 6 December 2012, Shankar was admitted to Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, San Diego, California after complaining of breathing difficulties. He died on 11 December 2012 at around 4:30pm PST. According to the The Ravi Shankar Foundation, Shankar had suffered from upper-respiratory and heart issues over the past year and underwent heart-valve replacement surgery on 6 December 2012.[66]

[edit]Discography

[edit]Bibliography

- Shankar, Ravi (1968). My Music, My Life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-20113-1.

- Shankar, Ravi (1979). Learning Indian Music: A Systematic Approach. Onomatopoeia. OCLC 21376688.

- Shankar, Ravi (1997). Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar. Genesis Publications. ISBN 0-904351-46-7.

[edit]Notes

- ^ "East Meets West MusicRavi Shankar Foundation". East Meets West Music, Inc. Ravi Shankar Foundation. 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Ganapathy, Lata (12 December 2012). "Pandit Ravi Shankar passes away". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Neuhoff 2006, pp. 672–673

- ^ a b c d e f Lavezzoli 2006, p. 48

- ^ a b c d e f Hunt, Ken. "Ravi Shankar – Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d Massey 1996, p. 159

- ^ Ghosh 1983, p. 7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Slawek 2001, pp. 202–203

- ^ Ghosh 1983, p. 55

- ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 50

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 51

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 52

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 53

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghosh 1983, p. 57

- ^ Sharma 2007, pp. 163–164

- ^ a b c Deb, Arunabha (26 February 2009). "Ravi Shankar: 10 interesting facts". Mint. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 56

- ^ Schickel, Richard (12 February 2005). "The Apu Trilogy (1955, 1956, 1959)". TIME. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ A lesser known side of Ravi Shankar Hindustan TimesDecember 12, 2012

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 47

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 57

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 58

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b c d Lavezzoli 2006, p. 61

- ^ a b c Brockhaus, p. 199

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 62

- ^ a b Schaffner 1980, p. 64

- ^ a b c d e Glass, Philip (9 December 2001). "George Harrison, World-Music Catalyst And Great-Souled Man; Open to the Influence Of Unfamiliar Cultures". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ a b Kozinn, Allan (1 December 2001). "George Harrison, 'Quiet Beatle' And Lead Guitarist, Dies at 58". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (24 November 1971). "Screen: Ravi Shankar; ' Raga,' a Documentary, at Carnegie Cinema". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Past Winners Search". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ a b O'Mahony, John (8 June 2008). "Ravi Shankar bids Europe adieu". The Taipei Times (UK). Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Ghosh 1983, p. 56

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 66

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 221

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 195

- ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 196

- ^ Rogers, Adam (8 August 1994). "Where Are They Now?".Newsweek. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 222

- ^ a b Piccoli, Sean (19 April 2005). "Ravi Shankar remains true to his Eastern musical ethos". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "'Rajya Sabha Members'/Biographical Sketches 1952 – 2003" (PDF). Rajya Sabha. 6 January 2004. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 197

- ^ "Shankar advances her music". The Washington Times. 16 November 1999. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 411

- ^ Idato, Michael (9 April 2004). "Concert for George". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Anoushka enthralls at New York show". The Hindu (India). 4 February 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Barnett, Laura (6 June 2011). "Portrait of the artist: Ravi Shankar, musician". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ Menon 1995, p. 220

- ^ "Archive > Annual Archives > 1957 > Prize Winners". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "SNA: List of Akademi Awardees – Instrumental – Sitar".Sangeet Natak Akademi. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "SNA: List of Akademi Fellows". Sangeet Natak Akademi. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "Padma Awards". Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ "राष्ट्रीय कालिदास सम्मान [Rashtriya Kalidas Samman]" (in Hindi). Department of Public Relations of Madhya Pradesh. 2006. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar – The 2nd Fukuoka Asian Culture Prizes 1991". Asian Month. 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Citation for Ravi Shankar". Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ van Gelder, Lawrence (14 May 1998). "Footlights". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Sir Ravi". Billboard (Nielsen Business Media, Inc.) 113(19): 14. 12 May 2001. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Watrous, Peter (16 June 1998). "Pop Review; Just Music, No Oedipal Problems". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Hard to say no to free love: Ravi Shankar". Press Trust of India. Rediff.com. 13 May 2003. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b Lindgren, Kristina (21 September 1992). "Shubho Shankar Dies After Long Illness at 50". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ^ a b Venugopal, Bijoy (24 February 2003). "Norah's night at the Grammys". Rediff.com. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ Jamkhandikar, Shilpa (6 December 2012). "It's Ravi Shankar versus daughter Anoushka at the Grammys". Reuters. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Melwani, Lavina (24 December 1999). "In Her Father's Footsteps". Rediff.com. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Signing up for the veg revolution". Screen. 8 December 2000. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Varga, George (10 April 2011). "At 91, Ravi Shankar seeks new musical vistas". signonsandiego.com. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar, Grammy-winning Indian sitar virtuoso, dies at 92". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

[edit]References

- "Shankar, Ravi" (in German). Brockhaus Enzyklopädie. 20 (19th ed.). Mannheim: F. A. Brockhaus GmbH. 1993. ISBN 3-7653-1120-0.

- Ghosh, Dibyendu (December 1983). "A Humble Homage to the Superb". In Ghosh, Dibyendu. The Great Shankars. Kolkata: Agee Prakashani. p. 7. OCLC 15483971.

- Ghosh, Dibyendu (December 1983). "Ravishankar". In Ghosh, Dibyendu. The Great Shankars. Kolkata: Agee Prakashani. p. 55.OCLC 15483971.

- Lavezzoli, Peter (2006). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1815-5.

- Massey, Reginald (1996). The Music of India. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-332-9.

- Menon, Narayana (1995) [1980]. "Shankar, Ravi". In Sadie, Stanley. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 17 (1st ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- Neuhoff, Hans (2006). "Shankar, Ravi". In Finscher, Ludwig (in German). Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik. 15 (2nd ed.). Bärenreiter. ISBN 3-7618-1122-5.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1980). The Boys from Liverpool: John, Paul, George, Ringo. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-416-30661-6.

- Sharma, Vishwamitra (2007). Famous Indians of the 20th Century. Pustak Mahal. ISBN 81-223-0829-5.

- Slawek, Stephen (2001). "Shankar, Ravi". In Sadie, Stanley. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 23 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

No comments:

Post a Comment